"There's something moving out of you

Your body and your skin

Like mist comes from the water

You can sense it

when the cold has clenched its claws

and alone you face what's coming"

(lyrics by Peter Gabriel, 'Love Can Heal')

Introduction

This is the third part of my cancer diary which covers the past month or so. It includes post-operation injections, living with a stoma and scans. It also includes sections on diet, finances, a shocking revelation and my emotional reaction to it. As before, I publish this because it is quite tiring to provide a running commentary, giving updates, so it is easier for me to collect my thoughts into a monthly diary such as this and share that. For family and close friends, of course, I will always answer questions as they have a more practical role in supporting me. All support is welcome though. Warning: As with parts one and two, continue to read if you want to, but please note that this third post contains lots of personal and intimate details.

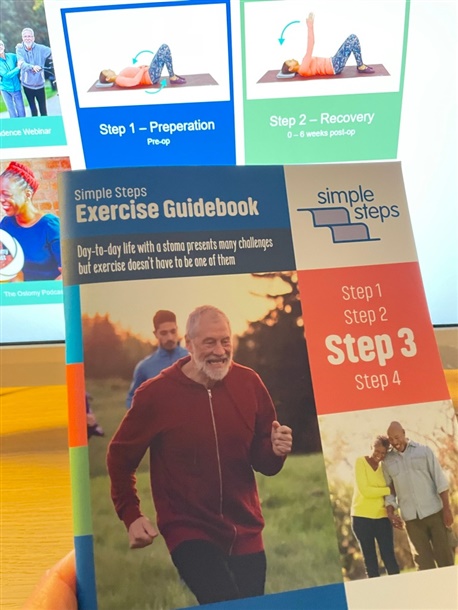

Information booklets from Macmillan and others

Post Operation

As I left hospital on 9 November, I was given some more Omeprazole for my non-erosive gastritis, although the inflammation might have reduced. I was also given 23 days supply of Dalteparin sodium (0.2ml) blood thinning solution. I bulked at this for two reasons. Firstly, whilst the risk of blood clots is possible following an operation, this is more likely when there is a severe lack of mobility. I was determined not to be bedridden or sitting around all day and wanted to get back to mild exercise. Secondly, without a regular, daily visit from a nurse, I would have to inject myself with a needle. This is not something I felt comfortable with. I sought advice from a nurse at my local GP, who guided me through doing my own injection for the first time. It is a minor fear, not complete trypanophobia. However, I was not prepared to overcome it every day for three weeks. I also questioned the need to give me a drug by this method. There are natural ways to thin the blood through diet and I began to research this. I weighed myself on 10 November. I found that a further 7lbs in weight had been lost whilst in hospital and was temporarily down to 10st (63.5 kg) exactly. I’ve not weighed this little since I was a teenager. I also have little ‘fat’ on my body, making injections potentially more tricky as muscles should be avoided. So, like Sherlock Holmes, I needed a solution for the solution.

Living with a Stoma

Before my discharge, a stoma nurse specialist needed to make sure I was comfortable with maintenance issues. She was the one who inserted the suppositories which literally got things moving. Since discharge, I have had three visits so far from a brilliant community stoma nurse. There didn't use to be such a thing. People who had recently had a stoma (colostomy) created would have to trudge back to hospital for after care and support, which caused problems, especially for those struggling to maintain theirs. I am grateful that this community nurse actually set up the outreach for the county of Norfolk and now has a team of four people, and is backed (sponsored) by manufacturers, Hollister and Dansac. People living with a stoma have shared with the company Secure Start that preventing leaks and helping keep skin around the stoma healthy, are at the top of their list of concerns. Peristomal skin, which is the outside area around your stoma, is very important to keep healthy and free from faecal infection. Irritated and painful skin around the stoma can be and should be avoided. Some blisters and soreness have appeared and disappeared. The supplies, including the well-designed closed (and drainable) bags and adhesive remover, are ordered through the Fittleworth company and are arranged on prescription through my GP surgery and, because of my cancer diagnosis, I am exempt from being charged. My financial situation is discussed further down.

Following the MRI, I visited the Big C Cancer Centre with my mum. This centre is based outside the oncology unit at the hospital. This was a first, drop-in session to find out more about what services they offered. This includes emotional wellbeing support, professional counselling services, complementary therapies such as massage and reflexology and dietary advice. It is a lovely heart-shaped, almost ‘C’ like building full of soft furnishings. I will make good use of this place, especially after getting treatment in the oncology unit nearby. Small Macmillan grants can be applied for through an agent who works here. I will discuss my finances later on.

The PET (Positron Emission Tomography) - CT (Computed Tomography) Scan on 17 November was not half as bad as the MRI. This one, jointly carried out by Alliance Medical, required a radioactive tracer being injected into my arm by a lad who had been doing so for 22 years, since he was 18 years old. But the actual scan – in the unit's brand new scanner – was quick and efficient – lasting only 10 minutes. A modern scanner can take between 320 and 640 'slices' of 1-2mm thickness. Despite a 6 hour fast and the hour long wait for the tracer to take effect, I was soon out and munching on liquorice in the car home.

During this week of scans I finished off a little, personal project of digitising an album I made 30 years ago, which included scanning old photos and diary entries to accompany a nostalgic post and video which I shared on 21 November. It is titled 'So Serious', which might now refer to my following prognosis.

Oncology Consultation

The very important consultation with my oncologist (cancer doctor) took place on 5 December. My sister-in-law accompanied me, took extensive notes and without her I would not have coped or retained the information given. I had tried to chase results of the scans beforehand to no avail. I was weighed beforehand and it was noted that I had managed to put on a few pounds. During an excellent and frank consultation, the oncologist confirmed the rectosigmoid tumour in the bowel and the disease in the liver, too. With the PET scan, the primary tumour could be seen, with the spread to liver and some lymph nodes, too. The lesions are part of the liver, not growths on the outside of it. The location of the biggest lesion is in the middle, the right hand side looking at it. The MRI scan showed this is now 92mm (previously 68mm) and still growing. This is the biggest concern as would be, in his words, 'life limiting'. We saw photographic evidence from the PET scan but could also see it needed an expert to make sense of the images. I tentatively asked for copies, but on this occasion was not given them. However, I returned a week later for a further endoscopy, which I describe below, and managed to obtain photographic evidence of the bowel tumour then.

The most shocking news came from a question which was asked towards the end. Up until now I have wanted facts, even if it means stating the worse case scenario. The prognosis for having advanced (stage 4) cancer is that this is 'inoperable'. The consultant didn’t know if we would be able to operate until after any chemotherapy and was worried that he might not be able to. Having no treatment at all would mean that I have an estimated 6 MONTHS TO LIVE from diagnosis, which was in early October. So, this effectively meant just I would only have a probable 4 MONTHS to live from the date of this consultation! If chemotherapy is carried out but not well enough to move to 'operable', then the prognosis for survival could be 12-18 months, with palliative treatment, but this could get to 24 months depending on response, fitness. Either of these painted worst case scenarios. The prospect suddenly looked incredibly bleak and worried me greatly. Regardless of how I got here, I knew that having no treatment at all was not an option. But I would also require significant healing. Short of an actual miracle, we turn to the drugs.

Chemotherapy is crucial and needs to be started with minimal delay. There have already been too many unavoidable delays. The aim is to control the disease and hopefully shrink the size of the tumours. If it can be shrunk enough they might be able operate. If not, it is life limiting and any drugs are about controlling it but curing it. Chemotherapy is described as neoadjuvant when that person with cancer receives before their primary course of treatment. (pre-operative). Or this is described as 'palliative' when the treatment is about control only. The drugs that will be administered are collectively known as FOLFOX. This consists of folinic acid (leucovorin) with oxaliplatin, with a separate infusion of fluorouracil (5FU). These would be given in hospital every 3 weeks at the start of each cycle. With one of the drugs the following week, and the other drug the week after that. I was facing at least 6 cycles (18 weeks) of this, with blood tests before every infusion. My general physical health and fitness weighs in my favour.

Collateral Damage

There are numerous side effects to be aware of. During the infusion you can feel pain along the vein or suffer with a throat spasm. These can be worse in cold temperatures, such as we have now. During treatment there is significant risk of infection, as white blood cells decreased. I would be left standing there defenceless. Neutropenic sepsis can occur and become life-threatening within hours. Fatigue is to be expected. Diarrhoea is common, which causes a stoma to be more active. Nausea leading to feeling sick, too. Peripheral neuropathy can also occur where you lose a sense of touch, numbness and tingling. You feel the cold more easily. It will clench its claws and I will need protection from cold things. Ice cream will be off the menu. There will be a need to wrap up warm, even more than usual at this time of year. I still have to breathe the air and get out in the sunlight. Of course, the infamous hair loss can also occur, but that is possibly the least of my worries and might not even happen. I portray the chemotherapy as a war on the body. In order to kill the 'bad guys' you have to take out some 'good guys' - so-called 'collateral damage'. But it is best not to focus on all the possible side effects and only react to those that actually happen. In that respect, I also worry that I might not react quickly enough to life-threatening symptoms, including delaying calling for emergency help.

Emotional Reaction

I had a massive emotional reaction to the consultation, firstly at the Big C Centre, then a couple of days later after we had sat down to type up the notes. My previously mild stomach cramps worsened, my anxiety skyrocketed and I begun to feel quite depressed, too, at the prospect of lengthy treatment and coping with the likely side effects. I've already panicked with overwhelming, racing thoughts, and it is likely this will happen again. More than anything, the shocking revelation that I would only have months to live, without treatment, showed just how advanced and life threatening my cancer is. The photos and images I've seen as evidence just made it all the more real. I feel vulnerable, scared, mortal, and invariably angry, anxious and depressed. I neglected to talk about my long experience of adverse mental health in the consultation, and I am reluctant to take any more medicine given what my body is about to be subjected to. My resilience, my mental resolve will be severely tested in the coming months, as I don't have much to look forward to. I worry about the practical support around me. This will be my biggest ever challenge, my biggest fight - if I am up for it, that is. Not just for me, but the strain it puts on my family is immense, too. Since the consultation, I have not felt as confident as I did earlier on about 'kicking its arse', despite knowing that we would have to try. I have always thought it better than to know how long you had left to live, rather than die suddenly. Then you could plan for things and, maybe, organise the rest of your life. Even if that is a scary prospect. We might only be able to delay it, not put it off indefinitely. I won't be able to do this alone, but I'm also struggling to ask for help. Early retirement also seems like a realistic prospect now. On that note, let's turn to the financial outlook.

The title and subject of my BA dissertation at Anglia [Polytechnic/Ruskin] University was 'Grey Matters: The Social Construction of Retirement Age'. I wrote this in about three weeks, when I was 30 years old, and it has suddenly become more pertinent to me. I still hope to have the remainder of my type 1 student loan paid off when I'm 60. But that is still some way off and I have begun looking into what benefits I would be entitled to IF I don't make it that far.

Financially, I should be fine. I put in a claim for Universal Credit back on 6 October. A health declaration was sent off on the same day as I originally went into hospital. This triggered a work capability assessment, too. Upcoming cancer treatment, which could lay me low for some time, maybe for 3-6 months. It will be a significant reason for not being able to hold down a job, but I still must not underestimate how bad things might get physically. The Universal Credit appointment by video on Thursday 16 November was straightforward, following an in-person the previous month. It has been totally accepted by the DWP that I will not be able to work for several months. I was asked about my condition and upcoming hospital appointments. Further video appointments confirmed I would not be required to look for work. A Work Capability Assessment claim was made and on 2 December, a letter arrived also stating that I had limited capability for work, would not be asked to search for work or need to supply additional 'fit' notes.

I have a small Teachers' Pension (accumulated through working at Norfolk County Council, The University of Sheffield and The University of Central Lancashire). I have stopped paying into my private pension, which I have been doing so on and off since I was 23 years old and worked at an insurance brokers in Fakenham. One of the three plans has a retirement age of 55, while the other two have a retirement age of 65. Until now, I had expected it to be at least the higher age. However, I might not even live to the lower age now. Apparently you can draw the money out early if you are given a terminal prognosis of 12 months or fewer. I never expected to be writing something that.

Conclusion

This third entry has covered everything that has led up to starting treatment for the cancer. It includes the prognosis for survival, and my emotional response. Much of what was discussed in the consultation was confirmed in a copy of a letter typed on 6 December, but not received until 15 December. I don't know if and when a fourth diary entry might be written. It depends on my energy levels. I might just post an occasional update on social media in the meantime. I will try to keep private notes just in case.

I was informed on 19 December by phone that a letter has been sent out stating that my chemotherapy will begin on 2 January - in Norwich. It feels simultaneously both soon and yet far away, given the urgency. That would be the start of the first cycle of treatment, with small doses each subsequent week - in Cromer or Dereham (to be decided) - until the next 3 week cycle which should start around 23 January. The result of my sigmoidoscopy revealed that I could be given the antibody, Cetuximab, *incorrectly described as an antibiotic when first posted, with effect from 24 January as I had the normal 'wild type' gene. A new schedule was given to me on 2 January.

Whatever cancer throws your way, we’re right there with you.

We’re here to provide physical, financial and emotional support.

© Macmillan Cancer Support 2025 © Macmillan Cancer Support, registered charity in England and Wales (261017), Scotland (SC039907) and the Isle of Man (604). Also operating in Northern Ireland. A company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales company number 2400969. Isle of Man company number 4694F. Registered office: 3rd Floor, Bronze Building, The Forge, 105 Sumner Street, London, SE1 9HZ. VAT no: 668265007